I have a friend who won’t eat dairy. This means I cannot offer her my mince pies. My mince pies have cheese in them and are delicious. So, I make them every year and have done for over 30 years. The recipe is not mine but instead is the work of the prolific Josceline Dimbleby from her 1978 book Cooking for Christmas.

This post was to have been a simple offering of her work, because there is no time at this point in the year to research, think and write. But then… Goodness, who knew that mince pies had such a history.

OK, so, Mincemeat Pies. The ‘mince’ part comes from a Latin word meaning “small”. The meat part is quite another matter. Here we go to history. Imagine something more like Moroccan pastilla, says Katherine Knowles, the pigeon or rabbit filo pie studded with almonds, scented with cinnamon, and dusted with powdered sugar. Variations on pies like this were popular all over the Middle East, down into Ancient Egypt, across to Greece and all the way to pre-Christian Rome, where spiced, sweet meat pies were an integral part of Saturnalia celebrations.

Then think Spice Road, Crusaders (1095-1492) returning to England with these expensive flavours (cinnamon, cloves, nutmeg, mace, dried fruits, citrus), and also the Christian celebrations into which they could be incorporated. Mince pies soon became a dish associated mainly with festivities, especially the celebrations of the Christmas season. During the twelve days of Christmas, Clements notes in her Brief History of Mince Pies, wealthy rulers and people often put on massive feasts, and an expensive dish of meat and fruit like a mince pie made a great way to show off one’s status. For instance, in 1413, King Henry V served a mincemeat pie at his coronation. Henry the VII, Walkers Shortbread tells us, was fond of the meaty Christmas pie as a main dish, filled with minced meat and fruit.

The shape changed over time as did the significance of the ingredients. Ellen Castelow tells us that, in the Tudor period (1485-1603), ‘they were rectangular, shaped like a manger and often had a pastry baby Jesus on the lid. They were made from 13 ingredients to represent Jesus and his disciples and were all symbolic to the Christmas story. As well as dried fruit such as raisins, prunes and figs, they included lamb or mutton to represent the shepherds and spices (cinnamon, cloves and nutmeg) for the Wise Men.’

Traditional ‘Baby Jesus in a crib’ mince pies

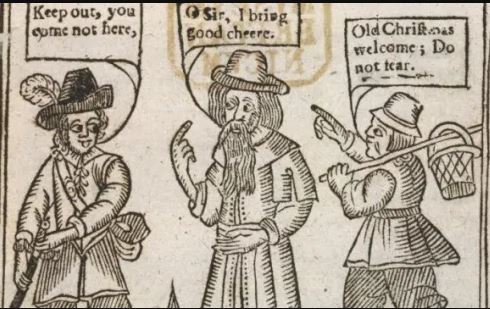

Cromwell

However, then came the Puritans. In 1645 Parliament abolished the holy feasts of Christmas (and also Easter and Whitsun), and anything associated with Christmas celebrations, including mince pies (and plum pudding). The History Jar says that ‘In January 1645 the Directory of Public Worship stated that ‘Festival days, vulgarly called Holy days, having no Warrant in the Word of God, are not to be continued’. In June 1647, following the Long Parliament victories, an ordinance banned Christmas, Easter and Whitsun. Fasting, normally practised on Christmas Eve, now became the norm for the entire period of the formerly happy 12 days. Oliver Cromwell, says The Mince Pie Club (yes, it really exists), Lord Protector of the Commonwealth of England, Scotland and Ireland (1653-58) is often erroneously said to be responsible for these legislation’s, however, he simply upheld existing Puritan law, of which, of course, he was an ardent supporter.

There was a ban on anything associated with Christmas celebrations, including mince pies and plum pudding. Soldiers even roamed the streets seizing food by force if they believed it be associated with a Christmas feast. And so came the so-called ‘Mince Pie Riots’, more accurately called the Plum Pudding Riots, but I am taking a bit of historical licence here – because both mince pies and plum pudding were on the ‘immoral, sinful, corruptible or non-Christian’ list.

The populace of various towns, Canterbury, Norwich, and Ipswich for example, rioted and indulged in civil disobedience – think, refusing to keep your shop open on Christmas day, or playing a game of football through the streets which just ‘happened’ to break some Puritans windows. But my favourite act of disobedience is flower arranging. In London apprentices took up flower arranging, sticking holly and ivy onto the water conduits at Cornhill. None of these acts went down well with the authorities but they did not stop, at least in Canterbury, until in January 1648, a band of Parliamentarian soldiers were dispatched to restore order, but by that time the protest had moved on and it was the people of Kent who were up in arms against Parliament.

In 1660, Charles, the Merry Monarch, restored the kingship. Along with the general atmosphere of national relief and religious tolerance he tried to promote, the rules put in place around the 12 days of Christmas were abolished and it was re-established as a religious and secular feast. Mince pies were on the menu again (although they had never really disappeared, only gone underground for a while).

Mince pies have been known under several names over the years. Christmas pyes indicate their popularity at this time of year, shrid pies refer to the shredded suet and meat, crib cakes which allude to baby Jesus in his crib, and wayfarer’s pies, as they were a traditional treat served to travelling visitors. The meat has changed over the centuries from lamb or mutton in the Medieval and Tudor times until in the 18th century it was more likely to be tongue or even tripe, and in the 19th century it was minced beef. These mincemeat pies were still on the savoury side. But Katherine Knowles tells us that in ‘1845, Eliza Acton wrote two recipes for mince pies: one, the typical meat mince pie we’ve been seeing thus far, with one pound of tongue (!); and another, with a lot more sugar and dried fruits, but where the only nod to carnivores is suet. She calls it “superlative.” Today we’d probably just call it “mincemeat.”’ Thus, began the mince pie that we are familiar with today.

It is only in the last 50 years or so, says Knowles, that suet has replaced meat, and only in the last decade has vegetarian suet become the default for commercially produced products.

But mincemeat need not be restricted to just Christmas mince pies. This week, the Guardian, invited chefs to tell us ‘what you can make with mincemeat apart from mince pies‘. The range is formidable, but then it may also presage a cultural shift in the traditional use of mincemeat for the mincemeat pie.

Here is ‘my’ recipe for mince pies. I hope you enjoy. Have the very best time over the holiday period that is possible to have in the present circumstances. Stay safe, stay healthy and come back to read more in 2021.

Weekly Recipe

Mince Pies

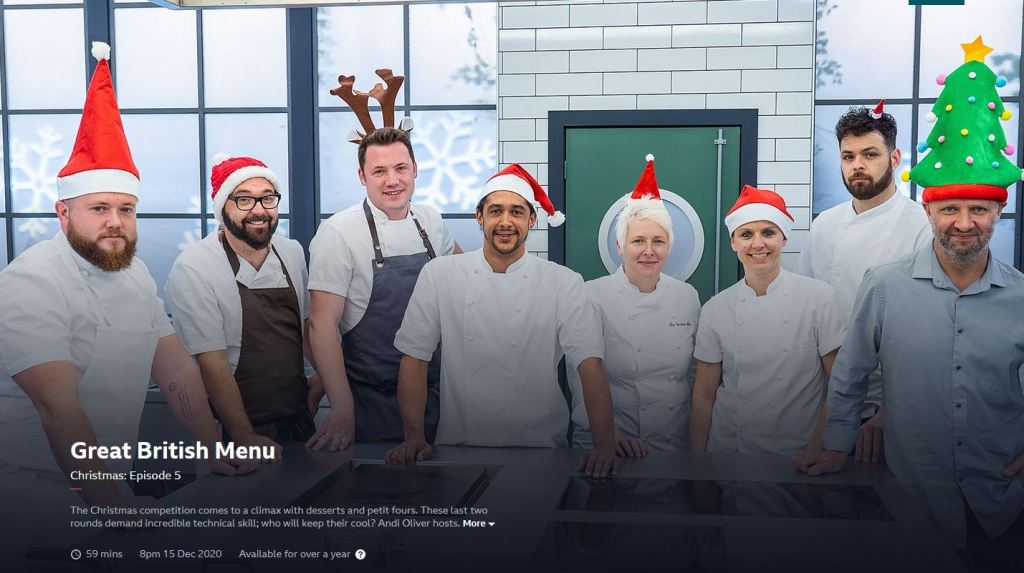

BREAKING NEWS!

Tommy Banks (of The Black Swan restaurant in Oldstead), seen here with other contestants and with judge Andi Oliver, has just won a course in the Great British Menu Christmas Special – and guess with what – root vegetable mince pies and sweet woodruff bourbon eggnog. Have a good one, everyone.