In my store cupboard I have an item, versions of which say they originate in Tahiti, Papua New Guinea, and the Cook Islands. I have no idea where others originated but most I know came with me from New Zealand and I can locate their origins firmly in the southern hemisphere. Some come in multiples from each location, and in pastes, pods and liquids. They are stored in anonymous or labelled pippetes, in bottles, in tubs, in a tube and in simple clear packaging. Most are ‘pure’ and have the longest ‘best by’ date (commonly 2035) you can imagine – I think it is notional. One paste is unadulterated and one has sugar, inulin and gum tragacanth added. You might think I have an obsession with this item, but no, I just like collecting really good versions of ingredients. Vanilla has given me plenty of opportunity for this.

Wikipedia has an excellent history of vanilla but briefly, one of the main origins of vanilla can be traced to the modern day state of Veracruz in Mexico. M. Holland (The Edible Atlas, 2014) tell us that it was, ‘first used by the Totomac people who were native to this area in the 15th century, but quickly spread to Europe with the arrival of the conquistadors who named it vanilla or ‘little pod’.

There are several types of vanilla. The Central American Vanilla inodora has no aroma, while the Vanilla pompona, from the West Indies, with shorter pods has an aroma of nutmeg. It is only the Vanilla planifolia which has the true fragrant aroma and it is indigenous to Central America, the Greater Antiles, and to the West Indies.

So here’s the thing with vanilla, pollination of vanilla flowers happens unaided only in Mexico and even then only with a small percentage of fruits. It was only in 1841 when Edmund Albius, aged 12 years old and living on Reunion, developed a practical method of pollinating vanilla that commercial cultivation became possible. Of course others falsely laid claim to his success but in the end all agree that a 12 year old slave is the one responsible for this development.

Coming from the cured pods of the Vanilla planifolia species, vanilla is a plant with thick, fleshy green stems and long leathery leaves (A History of Food, p846). It has small flowers which open for just eight hours, in the wild is pollinated by melipone bees and humming birds and develops long (up to 12inches) yellow-green pods. The pods develop within 4 weeks and the beans from these are then harvested when barely ripe. They are plunged into boiling water or exposed to the sun resulting in the seepage of a liquid which becomes dark when fermented. The pods are finally dried and are, accoring to Toussaint-Samat (A History of Food, Wiley-Blackwell, 1992) ‘they are seen to be covered with a fine frosting of crystals of vanillin or aromatic aldehyde’.

Vanilla is now mainly produced in Madagascar, the Comoro Islands, Reunion, Indonesia and, of course, Mexico. Although today, rare specimens are now available from the Malabar Coast of India, the Amazon rainforest and the Mexican Yucatán; Sri Lanka, Papua New Guinea, Tanzania, Uganda, Ecuador and Peru; and the islands of Oahu, the Marquesas and Vanuatu.

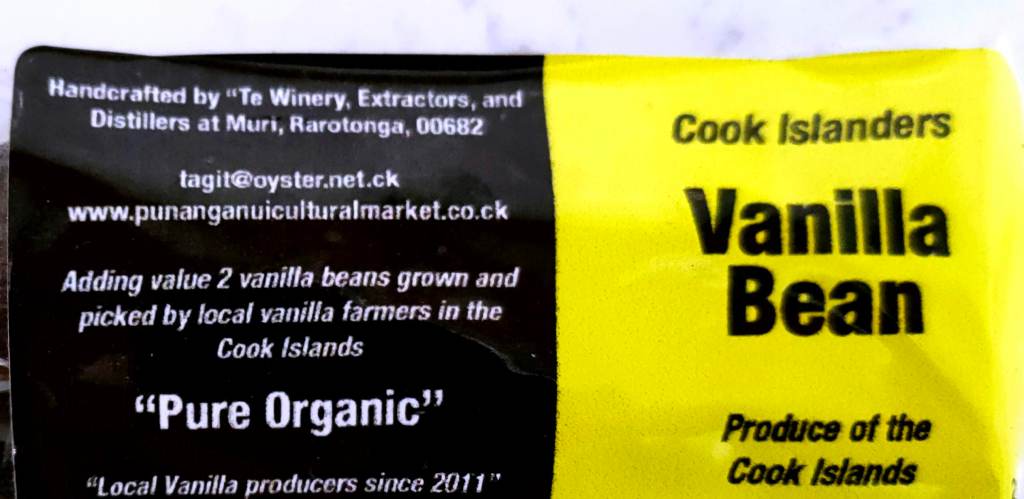

I first came across fresh vanilla, however, when I visited the Cook Islands and specifically Rarotonga. Vanilla has grown in the Cook Islands since its introduction there in 1942. The island produces ideal conditions for its growth. At that time it wasn’t grown commercially but rather as a hobby which might become a business. Lafala Turepu set up Turepu Vanilla in 2017 with an aim to produce a viable export product. She developed pastes, extracts and packs of vanilla. Today Turepu Vanilla is exported to the USA.

The sad thing is that almost none of the vanilla in global circulation comes from beans at all. More than 90 percent of the world’s vanillin — the chemical compound in vanilla that is predominantly responsible for its aroma and flavor — is artificially synthesized, mostly from guaiacol, a viscous oil commercially produced using petrochemicals, and a smaller amount from lignin, a waste product in the processing of wood pulp into paper (Ligaya Mishan). As an aside for all my booklover friends and librarians, Mishan notes that, ‘A trace of lignin may be found in every book’s pages, which may explain why antique bookstores and the musty back shelves of libraries smell so comforting as their volumes decay’.

From a profit perspective, the appeal of synthetic vanillin is clear. True vanilla is a demanding crop, so labor-intensive that at times the market value of the beans has surpassed that of silver, weight for weight. And since each bean yields only 2 percent vanillin at best, the cost of pure vanilla is even higher. In 2017, after a cyclone decimated farms in the mountains of northeast Madagascar, where around 80 percent of the world’s natural vanilla is grown, the price of beans leaped to more than $600 per kilogram, which, at the rate of 20 grams of vanillin per kilogram of beans, comes to $30,000 per kilogram of pure vanilla. As of 2012, 80.7 percent of the country’s population subsisted on $2.15 a day and, although the vanilla boom may have lifted incomes, it also radically inflated prices — a chicken was suddenly $10 — and sparked a proliferation of crime, with machete patrols required to protect the fields (as chronicled by Wendell Steavenson for NPR in 2019).

Mishan tells us that today, vanilla (artificial or genuine) appears in around 18,000 products worldwide. It seems ubiquitous, but that does not mean it is easy to identify. In a series of blind tests conducted by Cook’s Illustrated the experts preferred the fake (essence) vanilla for cakes, and were unable to detect much difference in bakes made with essence as opposed to genuine extracts. Depending on where the beans are harvested, vanilla may taste dark-sweet, of smoke and cherries; or earthy as chocolate and coffee; or buttery, or caramelly or plummy; or stung by the faintest numbing hint of anise. Tahitian vanilla has a cherry and anise flavour, while Mexican is spicier and richer.

It is used in all sorts of ways, with chocolate, ice-cream, cakes, biscuits, confectionary, alcoholic and non-alcoholic drinks and increasingly in savoury dishes. Today I give you a recipe that uses vanilla in a vinagarette. I liked the idea of combining balsamic vinegar with vanilla and so I tried it. Below is a simple recipe for the result. I hope you enjoy it.

Vanilla and Balsamic Vinagarette