What can I say, I was going to write about biscuits this week, and I have, even if not quite as I have been promising to do. But my eye got caught by, of all things, endocannibalism, and this led to food for funerals, and the rest, as they say is …..

Eating the other and feeding the other

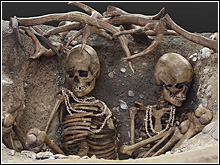

First, let’s get the cannibalism out of the way. The history of funeral food can be dated back to 12,000 years ago and the Paleolithic era. Scientists have found evidence of cannibalism and intentional ritual marking on bones from that time. It is felt that this was endocannibalism rather than exocannibalism. Exocannibalism, or revenge cannibalism, is the type seen at the end of a battle or war but endocannibalism is a ritual funeral practice to commemorate loved ones. Anthropologists, seeing this practice from these early times, through to today and in very different geographical locations (such as Papua New Guinea and the Amazon River Basin), hypothesise that it is a ritual that evolved in early before humans spread out across the planet. AND – it exists today – albeit in a symbolic form in the Christian ritual of communion in the eating and drinking of wafer and wine, symbolic of Christ’s body and blood.

The move from familial or tribal cannibalism to a ritual which used food symbolically to nourish the deceased can be dated back to about 4,000 years ago and Egyptian funeral practice. Sarah Lohman of the Wine History Project says that, ‘Food like bread and beer were left in tombs for the deceased for their spiritual nourishment. Paintings of cattle and birds on the walls would provide further sustenance once the worldly food ran out. We can see a transition at King Midas’ funeral, in 8th-century Anatolia (located in modern-day Turkey). A feast of goat stew and fermented beverages was presented in his tomb for his spiritual nourishment, but was then consumed by the funeral attendees. Then, the table, dinnerware, and leftovers were sealed in the tomb with Midas’ body.’ Sarah Lohman also says that, ‘Ancient cultures from African to Chinese buried their dead with pots of honey, and that ancient Greeks included honey cakes with which the deceased were supposed to bribe Cerebus at the gates of Hades’.

Food fit for mourners

The next major change was the use of food offerings, not to accompany the dead but rather to be shared by the mourners. What is offered in mourning varies across time and between cultures. In the Hindu faith baskets of fruit and vegetables are gifted to families, the Amish bring a raisin filled funeral pie, while in Sweden Funeral Glogg is used to toast the deceased. Rice is a symbol of life in Asian cultures and is included in all funerals. The eating of chicken, in China for instance, symbolically helps the soul of the dead to fly to heaven. Again in China the eating of sugar, in the form of sweets/candies, handed out after a funeral, is meant to purify mourners after coming into contact with the dead.

In Europe, wheat, as a symbol of the cycle of life and part of the funeral service can be dated back 2,000 years, in the use of Coliva – death or corpse cake. It was made from boiled wheat and shaped to resemble a grave mound and then sprinkled with sugar before being decorated with nuts or dried fruits. Emerging from the Middle Ages in Germany, this funeral tradition of eating ‘corpse cakes’ symbolically mirrored the act of eating the deceased. After the body had been washed and laid in its coffin, the woman of the house prepared leavened dough and placed it to rise on the linen-covered chest of the corpse. It was believed the dough “absorbed” some of the deceased’s personal qualities that were, in turn, passed on to mourners who ate the corpse cakes.

Pity the sin-eaters, sacred and profane

Echoes of this tradition can also be found in the later practice of sin-eating, as well as the even later consumption of arvel cakes—more of a rich, slightly sweet bread. In Celebrating Life Customs Around The World: From Baby Showers To Funerals, author Victoria Williams describes how ‘the absorption of the traits of the dead’ can be observed in the practice of sin-eaters found in China as well as Europe. In China, families can ask monks to transfer the sins of the dead to dim-sum dishes. These dishes are then eaten by ‘sin-eaters’.

In England and Ireland, from the 17th to 20th century, bread and salt would be left on a corpse to be eaten by ‘a person of the lowest possible social standing’. Historic Camden County says that,

‘The local sin-eater was a reviled person of the lowest social status – not unlike the untouchables of India or burakumin of Japan – who was paid a pittance to attend the wake and eat bread and salt from a plate or bowl resting on the chest of the deceased. In doing so, he was believed to be consuming and transferring the sins of the dead to himself, allowing the departed soul to enter heaven rather than be forced to wander the earth to atone for wicked deeds. Period accounts indicate that once the sin-eater finished the plate, he was often kicked, punched and otherwise abused by the crowd as he scrambled to escape the gathering.’ They go on to say that ‘Afterward, the mourners would be given arvel cakes flavored with caraway seeds to represent new life, and that this was served over the corpse by the bereaved family.’ This tradition of ‘serving over the corpse’ is in direct contrast to Maori traditions:

In the Maori culture no food (considered ‘noa’ or ordinary) could ever be passed or served over a corpse because a corpse is considered ‘tapu’ or sacred. Because a person’s head is a tapu part of the body and food is noa, you can never pass food (such as a plate or tray) over a Māori person’s head (dead or alive), because that action can strip them of all personal tapu.

Anything to do with death is also tapu. The presence of the dead body makes the room tapu, and therefore food and drinks cannot be brought into the room. Only after burial rites are completed is food approached, a hakari or feast is held. The home of the deceased and the place where the deceased died are ritually cleansed with karakia (prayers or incantations) and de-sanctified ‘with food and drink, in a ceremony called takahi whare, or trampling the house’.

Let them eat cake …. or biscuits

To return to the traditiions around the 17th-19th century departed sin-eater: Family members stood on one side of the coffin and handed chunks of “arval” or “arvil” cake across the corpse to mourners. The practice traces back to the Nordic tradition of hoisting bowls of “heir ale” (Arval = succession ale) at funerals to toast the oldest male’s assumption of the family property and power. The English avril, arvil, arval or ale cakes were often washed down with spiced ale or port before the pallbearers carried the body to the burial site.

Alison Petch of The Pitt Rivers Museum in Oxford, has written about the different traditions that existed in England concerning funeral food and distinguishes between those foods which are to be consumed at the funeral, perhaps before, perhaps after interment, and those which are gifted to the mourners and can be taken home. Records from 1778-80 show that an Arthel or Arvel dinner is held on the Day of Interment to which friends and family of a wealthy corpse are invited; in 1807 this arval or arvil supper is the opportunity to distribute arval-bread amongst the poor and in 1875 we learn that these Averill funeral loaves are spiced with cinnamon, nutmeg, sugar and raisins.

Funeral cake marker, My Learning

Image: H.Levins 2011

Image: H.Levins 2011

In Cumberland, the mourners are each presented with a piece of rich cake, wrapped in white paper and sealed, ‘a ceremony which takes place before the ‘lifting of the corpse,’ when each visitor selects his packet and carries it home with him unopened, and in some parts of Yorkshire, a paper bag of biscuits, together with a card bearing the name of the deceased, is sent to the friends.’ [England Howlett F.S.A. “Burial Customs” (Curious church customs and cognate subjects) Edited by Wm. Andrews, quoted in Puckle, 1926: 109)]

She quotes from T.G.Barnett, 1919, that, ‘The custom of distributing to the mourners at a funeral specially prepared biscuits in wrappers sealed with black wax, was formerly widely prevalent in Great Britain. It was, probably, related to or derived from the earlier practice of “sin-eating”… More remotely, the practice may be an altered survival of ceremonial cannibalism when the flesh of dead kinsmen was eaten by the mourners.’ The biscuits were formerly called avril, arvil or arval bread.

And so we return to biscuits. Funeral biscuits were a thriving business from the 18th to the 20th century, notes Hoag Levins in 2011. Although they varied widely in size, shape and consistency, in spirit they were all the same. The wealthier English, says Levins, tended to favor the use of the sponge cake-like Lady Finger biscuits. These were wrapped in plain paper held together with a daub of black sealing wax.

Funeral biscuits were a staple of the bakery business. Some bakers’ newspaper advertisments addressed the suddenness with which most people had to organize funeral details and promised “funeral biscuits made to order on the shortest notice.” The wrappings served as a keepsake of the event itself.

But, by the time of WW1, for most, these Victorian traditions were replaced by the mass marketing of funeral homes and of funeral foods. We still feed the mourners, we still mourn the deceased, but can we call it symbolic cannibalism? Perhaps that is another story for another post.

Weekly Recipe