Do you like food that has been roasted, or caramelized, that has been fermented or cured? Do you like asparagus, tomatoes, kombu? How about marmite, miso and mushroom powder? Answering yes to some or all of these means you have experienced the fifth element of taste, umami.

Umami was first identified by Oriental cooks over 1200 years ago. It was not until the turn of 20th century that scientist’s isolated glutamate and other substances, which convey this distinctive flavor. In 1908, Kikunae Ikeda of the Tokyo Imperial University identified it. Professor Ikeda found that glutamate had a distinctive taste, different from the usual four tastes of sweet, sour, bitter and salty, and he named it “umami”.

Ikeda had noticed this particular taste in asparagus, tomatoes, cheese and meat, but it was strongest in dashi – that rich stock made from kombu (kelp) which is widely used as a flavour base in Japanese cooking. So he homed in on kombu, eventually pinpointing glutamate, an amino acid, as the source of savoury wonder. He then learned how to produce it in industrial quantities and patented the flavour enhancer MSG.

But why do we value it? One theory is that we evolved to favour umami-rich foods because they delivered all-important—and sometimes scarce—protein. Like the other basic tastes, detecting umami could be essential for survival. Umami compounds are typically found in high-protein foods, so tasting umami tells your body that a food contains protein. In response, your body secretes saliva and digestive juices to help digest these proteins. Another theory about the appeal of umami is that, because breast milk is high in glutamate, we might develop a lifelong desire for this taste beginning within hours of birth.

Now comes the science! Umami actually comes from glutamates and a group of chemicals called ribonucleotides, which also occur naturally in many foods. Scientifically speaking, umami refers to the taste of glutamate, inosinate, or guanylate. Glutamate — or glutamic acid — is a common amino acid in vegetable and animal proteins. Inosinate is mainly found in meats, while guanylate is more abundant in plants. The umami taste comes from the presence of these compounds which are typically present in high protein foods.

When you combine ingredients containing these different umami-giving compounds, they enhance one another so the dish packs more flavour points than the sum of its parts. So, the overall umami level of any given food depends more on the combined effect of glutamate with other umami compounds. For instance, the concentration of glutamate in sturgeon caviar is five times that in ikura (marinated salmon roe), but ikura has the more umami taste, because it also contains a small amount of inosinate, where caviar has none.

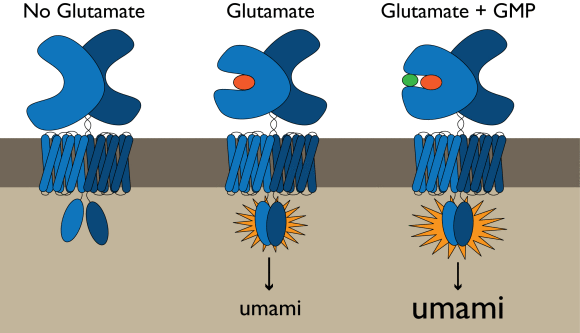

But there is more! Only relatively recently have the taste receptors (on the tongue) activated by glutamate been identified. This has allowed research into these receptors and umami intensification.

It has also been found that three known umami taste receptors can interact with both glutamate and a nucleotide called GMP to intensify the umami sensation caused by glutamate.

Because umami taste receptors are similar to the taste receptors for sweet and bitter, understanding how molecules like GMP enhance umami sensations will, inevitably, encourage the development of enhancers for other taste sensations. Identifying more taste enhancing molecules like GMP could bring a whole new dimension to the way we cook in the future.

Paul Breslin of Monell University says one of his key motivations is finding ways through taste research to feed malnourished people. “What you want,” he says “are things that are very tasty that kids will eat, that will go down easy and will help them.” Meanwhile, Professor Margot Gosney, who chairs the Academic and Research Committee of the British Geriatrics Society is “looking into increasing the umami content in hospital food,” to make it more appealing to older people, without overdoing the salt.

We all use umami in the context of our country’s food. Europe and America have bold flavors. Japan’s are more subtle. Kazu Katoh, the president of the Organization to Promote Japanese Restaurants Abroad (J.R.O.) says umami is the foundation of Japanese cuisine. He acknowledged that umami exists around the world: in the tomatoes and Parmesan cheese of Italy, for example, and in the miso, soy sauce, sake, and vinegar of Korea and China. The difference, according to Katoh, is rooted in geography. Japanese umami starts with Japanese terroir: “The temperature, and the moisture in the air. Vegetable growing, water, the dirt, the earth—it’s all important.” Then there’s technique: “The brewing and aging processes involved.” Additionally, “Japanese cooking is very, very simple. It’s about extracting. However, in French cooking”, he said, “it’s all about adding. It’s about adding sauces, cooking it in bouillon, using oil, pouring more dressing on it”.

So, says Stephani Lim from Epicurus, when you’re looking to dial up the savoury side of dishes, there are many, many ingredients that offer tons of umami while also lending additional layers of interest to whatever you’re cooking. Some foods are high in umami compounds such as aged cheeses, seaweeds, soy foods, mushrooms, tomatoes, kimchi, green tea, marmite, corn, green peas, garlic, lotus root and potatoes. Techniques too can add umami. Stephanie tells us that, roasting, caramelizing, browning and grilling all boost umami because they free glutamate from proteins. Processed foods such as those which are fermented also increase the umami content. Using fermented black beans or olives when making vegetable stock, adding a little bit of umeboshi paste to just about anything really makes its flavor sparkle. Alternatively, you can also add a dab of miso paste, nutritional yeast, or some porcini mushroom powder into the base of sauces or soups. Or do you want to make mushrooms taste like bacon? Add maple syrup and smoked salt and you’re there. More unusually, Korean soy sauce, made with jujube, kelp, and black beans can be added to chocolate icing, maple syrup for pancakes, and fresh cucumbers.

As Hannah Goldfield, The New Yorker’s food critic, says, umami is a cultural cipher, a malleable, claimable standard of identity, innovation, and taste. Umami is a badge of pride, once Japanese, now universal. A state of mind. Deliciousness. There is no recipe this week but I leave you with a photo of tonight’s dinner and challenge you to count how many different types of umami there are.

Finally, watch this space – there is a sixth taste being proposed, ‘kokumi’. Again a Japanese idea, its function, like umami, is to heighten other taste sensations. Food rich in calcium are said to be the best source.